A Protocol data unit (PDU) represents a single unit of data transmitted across a network. It acts as a digital container for information moving between different layers of network architecture. For example, in a data center, every piece of information exchanged between servers or storage devices travels within a PDU. This structured approach helps mitigate common communication errors, such as frame errors at the data link layer or lost segments at the transport layer. While a basic PDU simply carries data, an intelligent PDU offers advanced monitoring and control capabilities within complex network infrastructures.

Key Takeaways

- A Protocol Data Unit (PDU) is a basic data container. It moves information across a network.

- PDUs have three main parts. These are the data payload, header, and sometimes a trailer.

- Each layer of the OSI model uses a different PDU. Examples include bits, frames, packets, and segments.

- Encapsulation adds information to data. This happens as data moves down network layers.

- Decapsulation removes information from data. This happens as data moves up network layers.

- PDUs are important for network communication. They help with structured data exchange and error checking.

- PDUs ensure data integrity. They use tools like checksums to find errors.

- PDUs help different devices work together. They provide a common way to send data.

What is a Protocol Data Unit and Its Core Components?

What Exactly is a Protocol Data Unit?

Defining the Network’s Data Container

A Protocol Data Unit (PDU) serves as a fundamental data container within network communication. It encapsulates data for transmission across various network layers. Think of it as a specialized package for digital information. This structured approach ensures orderly data handling.

The Role of PDUs in Communication

PDUs facilitate organized and reliable data exchange between network devices. They ensure data travels correctly from its source to its destination. Each layer of the network model processes and modifies these units. For instance, in a data center, every piece of information exchanged between servers travels within a PDU.

What are the Main Components of a Protocol Data Unit?

The Data Payload

The data payload represents the actual information a user sends. This could be an email, a web page, a video stream, or any other application data. It forms the core content of the Protocol data unit. Network devices prioritize the efficient delivery of this payload.

The Header Information

The header precedes the data payload. It contains crucial control information for network devices. PDU headers are essential for network communication. They contain control information that ensures user data can traverse the network correctly and be reassembled at its destination. Without this control data, the user data would not be able to reach its intended recipient or be understood upon arrival. Each network layer adds its own header (and sometimes trailers) during encapsulation, forming a new PDU. This layered approach guarantees that the data is handled correctly by the corresponding layer on the receiving end, facilitating proper communication across the network.

Specific functions of a PDU’s header include:

- Source and destination addresses: These direct the data to the correct sender and receiver.

- Sequence numbers: These order data packets and reassemble them correctly at the destination.

- Error checking codes: These allow for the detection of errors that may occur during transmission.

- Protocol identifiers: These indicate which protocol is being used, enabling the receiving system to process the data appropriately.

The Trailer Information

The trailer follows the data payload. Not all PDUs include a trailer; it is most common at the data link layer. Trailers ensure errors are detected and corrected. This guarantees data moves smoothly through the network and reaches its destination without issues. They add extra error-checking capabilities to ensure data integrity.

Trailers, used in certain PDUs like those at the data link layer, provide error-checking capabilities. These include checksums or CRCs, which help detect any corruption that might occur during transmission. Ethernet frames, common network protocols at the data link layer, consist of CRC for error detection. The trailer signals the end of the packet. It often includes error-checking data like CRC. The receiving device uses the trailer to verify correctness before reassembling the original message.

How Do Protocol Data Units Relate to the OSI Model?

Understanding PDU Interaction with OSI Layers

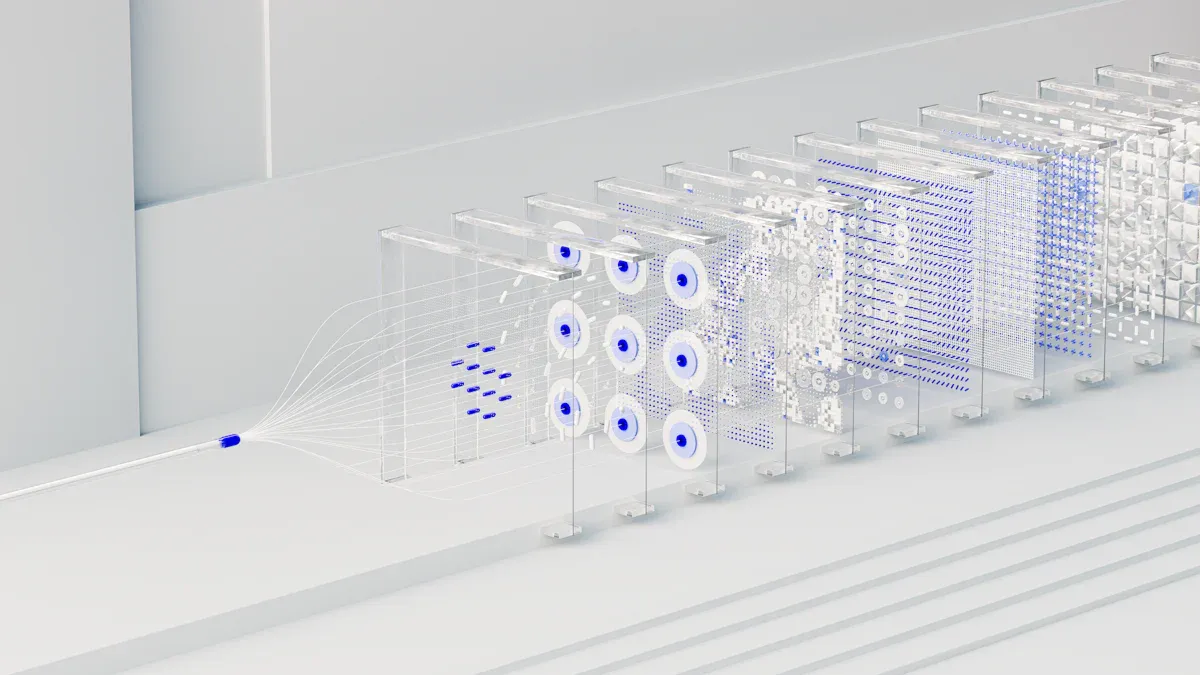

The Open Systems Interconnection (OSI) model provides a conceptual framework for network communication. It divides network functions into seven distinct layers. Protocol Data Units (PDUs) are central to this model, representing the specific data format at each layer. Each layer processes data and transforms it into its own PDU before passing it to the next layer.

Layer-Specific Data Units

Each layer within the OSI model handles data in a unique way, creating its own specific Protocol data unit. As data moves down the layers during transmission, each layer adds its own header and sometimes trailer information. This process is called encapsulation. When data reaches its destination, the reverse process occurs as each layer removes its corresponding header information during decapsulation.

Consider the journey of data from an application on a server in a data center.

- Application Layer: This layer generates the initial application data.

- Presentation Layer: It encapsulates the application data, preparing it for the session layer.

- Session Layer: This layer adds its own control information, passing the unit to the transport layer.

- Transport Layer: It encapsulates the data into a segment or datagram, sending it to the network layer.

- Network Layer: This layer forms a packet, adding logical addressing, and forwards it to the data link layer.

- Data Link Layer: It creates a frame, including physical addresses and error detection, then sends it to the physical layer.

- Physical Layer: This layer converts the frame into raw bits for transmission across the network medium.

At the receiving end, the decapsulation process reverses these steps. Each layer removes its specific header and trailer, extracting the data for the layer above, until the original application data reconstructs at the application layer. This structured approach ensures data integrity and allows each layer to perform its specialized tasks.

Peer-to-Peer Communication Between Layers

While data moves vertically through the layers on a single device, each layer conceptually communicates with its “peer” layer on the receiving device. The PDU created by a specific layer on the sending device is only fully understood and processed by the identical layer on the receiving device. For example, a network layer packet from a source server in a data center travels across the network. The destination server’s network layer processes that packet, not its data link or transport layer directly.

This model ensures a clear and organized process for handling data transmission and reception. It highlights the critical role of each layer in maintaining the integrity and efficiency of network communications.

Transmitting Device:

Layer N (PDU) -> Layer N-1 (SDU -> PDU) -> Layer N-2 (SDU -> PDU) -> … -> Layer 1 (Physical Transmission)

Receiving Device:

Layer 1 (Physical Reception) -> Layer 2 (PDU -> SDU) -> Layer 3 (PDU -> SDU) -> … -> Layer N (Original Data)

This peer-to-peer interaction, facilitated by layer-specific PDUs, allows for modularity and interoperability across diverse network systems.

What is a Segment Protocol Data Unit?

The Transport Layer’s PDU Explained

The transport layer in the OSI model handles end-to-end communication between applications. Its Protocol Data Unit (PDU) is known as a segment when using the Transmission Control Protocol (TCP). When using the User Datagram Protocol (UDP), the PDU is called a datagram. This layer ensures reliable and efficient data transfer between processes running on different hosts. For instance, when a server in a data center sends a large file to a client, the transport layer breaks that file into smaller segments.

Segment Function in Data Transmission

Segments play a crucial role in breaking down application data into manageable chunks. This process allows for efficient transmission across the network. Each segment includes a header with information vital for reassembly at the destination. The transport layer uses two primary protocols, TCP and UDP, each with distinct PDU characteristics.

| Protocol | PDU Name | Connection Type |

|---|---|---|

| TCP | Segment | Connection-oriented |

| UDP | Datagram | Connectionless |

TCP segments establish a connection before data transfer. They guarantee delivery and order. UDP datagrams offer a faster, connectionless service. They do not guarantee delivery or order. Applications choose the protocol based on their reliability requirements. For example, a data center might use TCP for database replication to ensure data integrity. It might use UDP for real-time monitoring data where speed is more critical than guaranteed delivery.

Connection and Flow Control Mechanisms

TCP segments implement robust mechanisms for connection establishment, flow control, and error recovery. Before sending data, TCP performs a three-way handshake to establish a connection. This ensures both sender and receiver are ready. Flow control prevents a fast sender from overwhelming a slow receiver. It manages the rate of data transmission.

Error control mechanisms ensure reliable delivery. These include sequence numbers and acknowledgments. If a segment does not arrive, the sender retransmits it. The TCP segment header contains many fields that facilitate these functions.

| Field Name | Description |

|---|---|

| Source Port | Identifies the sending application’s port. |

| Destination Port | Identifies the receiving application’s port. |

| Sequence Number | Orders data bytes within the segment for reassembly. |

| Acknowledgement Number | Confirms receipt of data and indicates the next expected byte. |

| Control Flags | Manage connection state (e.g., SYN for synchronize, ACK for acknowledge, FIN for finish). |

| Window Size | Advertises the receiver’s available buffer space for flow control. |

| Checksum | Detects errors in the segment header and data. |

| Urgent Pointer | Points to urgent data within the segment. |

These fields allow TCP to maintain a reliable, ordered, and error-checked data stream. This is essential for applications requiring high data integrity, such as financial transactions or critical data transfers within a data center.

What is a Packet Protocol Data Unit?

The Network Layer’s PDU Explained

The network layer in the OSI model manages the routing of data between different networks. Its Protocol Data Unit (PDU) is known as a packet. Specifically, when using the Internet Protocol (IP), this PDU is often called an IP datagram. Packets are fundamental for internet communication. They allow data to travel from a source device to a destination device across various interconnected networks. For example, when a server in a data center sends data to a client located in a different city, that data travels as a series of packets.

Packet Function in Routing

Packets perform a critical function in routing. They carry the necessary addressing information that allows routers to direct them across complex networks. When a data packet arrives at a router, the device consults its routing table. This table contains routes to different networks. The router determines the best available route based on factors like proximity to the destination, network load, and organizational policies.

The operating system first determines if the destination address is directly reachable on the local network. If not, it requires a router to reach a remote network. This analysis involves examining the destination IP address against the computer’s network configuration. The process starts with a subnet mask comparison. This defines the boundaries of the local network segment. For remote destinations, the operating system consults its routing table. This database maps network destinations to next-hop addresses or interfaces. The routing table acts as a roadmap for non-local traffic. It specifies where packets should be sent based on their destination addresses.

Routers forward IP datagrams from source to destination across interconnected networks. A host on the first LAN sends an IP datagram to a destination on the second LAN, addressing it to the remote host’s IP. The source host’s default gateway, which is the router, receives the packet. The router performs a table lookup on the destination IP to select the interface toward the second LAN. The router then decrements the Time to Live (TTL) field in the packet header. Finally, the router forwards the datagram, enabling communication across the networks.

Logical Addressing and Pathfinding

Packets rely on logical addressing for pathfinding. This means they use IP addresses to identify source and destination devices. Unlike physical MAC addresses, which operate within a local network, IP addresses allow packets to traverse the global internet. The IP header contains crucial information for this process.

An IPv4 packet header consists of several important fields:

- Version: Indicates the IP version (e.g., 4 for IPv4).

- Total Length: Specifies the entire size of the IP packet, including the header and data.

- Time to Live (TTL): An 8-bit field. Each time the packet passes through a router, the router decrements this value by 1. If it reaches 0, the packet is dropped. This prevents packets from looping infinitely on the network.

- Protocol: Identifies the upper-layer protocol (e.g., TCP, UDP) that the IP packet’s payload belongs to.

- Source address: A 32-bit field storing the IPv4 address of the sending device.

- Destination address: A 32-bit field storing the IPv4 address of the destination device.

These fields allow routers to make intelligent forwarding decisions. They ensure packets find the correct path through the network. This structured approach guarantees efficient and reliable delivery of data across diverse network types and topologies.

What is a Frame Protocol Data Unit?

The Data Link Layer’s PDU Explained

The data link layer, the second layer of the OSI model, manages data transfer between directly connected network nodes. Its Protocol Data Unit (PDU) is known as a frame. Frames are crucial for organizing bits of data into a structured format for transmission across a local network segment. For example, within a data center, every piece of information moving between servers on the same switch travels as a frame. This layer ensures reliable communication over a physical link.

Frame Function in Local Networks

Frames perform essential functions within local area networks (LANs). They encapsulate network layer packets (like IP packets) and prepare them for physical transmission. A frame adds specific control information, including physical addresses and error-checking data, to the packet. This ensures accurate delivery to the correct device on the local segment.

An Ethernet frame, a common type of frame, consists of several standard components that facilitate this process:

- Preamble (7 Bytes): This sequence of alternating 1s and 0s synchronizes the receiving device’s clock.

- Start Frame Delimiter (SFD) (1 Byte): It marks the end of the preamble and signals the beginning of the frame payload with a specific bit sequence (10101011).

- Destination MAC Address (6 Bytes): This specifies the MAC address of the intended recipient device.

- Source MAC Address (6 Bytes): This indicates the MAC address of the device sending the frame.

- EtherType/Length (2 Bytes): This specifies either the protocol type in the payload or the length of the payload data.

- Payload (Variable): This contains the actual data being transmitted, ranging from 46 to 1500 bytes.

- Frame Check Sequence (FCS) (4 Bytes): This 32-bit field identifies transmission errors.

The Preamble, a 7-byte sequence of alternating 1s and 0s, is crucial for synchronizing the clocks of sending and receiving devices. It is followed by the Start Frame Delimiter (SFD), a 1-byte field with a specific bit pattern (10101011) that signals the start of the actual frame. The Destination MAC Address and Source MAC Address, each 6 bytes, are unique identifiers for the recipient and sender, respectively, enabling accurate frame delivery within a LAN. The EtherType/Length field, a 2-byte segment, indicates either the protocol encapsulated in the payload (Ethernet II) or the payload data’s length (IEEE 802.3). The Payload is the core data, ranging from 46 to 1500 bytes, with padding added if necessary to meet minimum length requirements. Finally, the Frame Check Sequence (FCS), a 4-byte field, uses a cyclic redundancy check (CRC) value for error detection, ensuring data integrity by allowing the receiving device to identify corrupted frames.

Physical Addressing and Error Detection

Frames utilize physical addressing, specifically Media Access Control (MAC) addresses, for local delivery. Each network interface card (NIC) possesses a unique MAC address. This address ensures that a frame reaches its intended recipient on the same local network segment. Unlike IP addresses, which routers use for global routing, MAC addresses operate only within the local network.

Error detection is another critical function of frames. The data link layer implements mechanisms to identify corrupted frames during transmission. Ethernet employs a Cyclic Redundancy Check (CRC) technique within the trailer of each frame for error detection. The receiving device computes the CRC of the incoming frame and compares it against the CRC value in the trailer to identify any transmission errors. If the CRC values do not match, the receiving device discards the frame, indicating a transmission error. This ensures data integrity on the local network.

Tip: While CRC is widely used for error detection in Ethernet frames, simpler techniques like parity bits also exist. Parity bits involve adding a bit to ensure the count of ’1′s in the frame is either even or odd, providing a basic level of error checking.

What is a Bit Protocol Data Unit?

The Physical Layer’s PDU Explained

The physical layer, the lowest layer of the OSI model, handles the actual transmission of raw data bits across a physical medium. Its Protocol Data Unit (PDU) is simply a bit. A bit represents the most fundamental unit of information in digital communication, a binary 0 or 1. This layer focuses on the electrical, mechanical, procedural, and functional specifications for activating, maintaining, and deactivating physical links. For example, when data travels between servers in a data center, the physical layer converts all the complex frames and packets into a stream of individual bits for transmission.

Bit Function in Raw Data Transmission

Bits perform the essential function of carrying raw data across the network medium. Digital encoding at the physical layer transforms binary data (1s and 0s) into signals suitable for transmission. This process is crucial because raw binary data cannot be directly sent. For instance, in copper cable networks, binary data converts into electrical pulses. In fiber optic networks, it transforms into light patterns, and in wireless networks, into specific radio wave patterns. Different encoding methods are used depending on the medium. Electrical signals use methods like Manchester encoding and Non-Return-to-Zero (NRZ), while optical signals use On-Off Keying (OOK) and Pulse-Position Modulation (PPM).

Fiber optic cables, common in data centers for high-speed links, consist of thin glass strands. Each strand has a pure glass core that transmits light pulses. Transmitters convert digital data (binary 1s and 0s) into corresponding light pulses. These light pulses then travel along the fiber core to receivers at the other end, which decode them to reconstruct the original binary data.

Electrical and Optical Signals

The physical layer represents bits through various electrical or optical signals. For example, to transmit bits over an electrical wire:

- On the sender side:

- A bit ’1′ transmits by setting the voltage on the electrical wire to +5V for one millisecond.

- A bit ’0′ transmits by setting the voltage on the electrical wire to -5V for one millisecond.

- On the receiver side:

- Every millisecond, the system records the voltage on the electrical wire.

- If the voltage is +5V, the system records a bit ’1′.

- Otherwise, if the voltage is -5V, the system records a bit ’0′.

More advanced encoding schemes exist for higher data rates. Quadrature Amplitude Modulation (QAM) is a dominant protocol for encoding digital data onto analog carrier waves, especially for higher speed and/or longer distance communication. QAM modulates the carrier wave’s amplitude and phase to represent different bit patterns. For instance, 256QAM uses 256 different waveforms (symbols), each with a unique combination of phase and amplitude, to represent 8 bits per symbol. This technique is widely used in protocols like DSL and cable modems, and in long-distance Gigabit Ethernet standards within large network infrastructures.

Other common encoding schemes include:

- Non Return to Zero (NRZ): This method represents 1s with a high voltage level and 0s with a low voltage level, maintaining constant voltage during the bit interval.

- NRZ-L (NRZ Level): Polarity changes only when the incoming signal changes from 1 to 0 or 0 to 1.

- NRZ-I (NRZ Inverted): A transition occurs at the beginning of the bit interval for a 1, and no transition for a 0.

- Bi-phase Encoding: This method checks the signal level twice per bit time (initially and in the middle), with the clock derived from the signal itself.

- Bi-phase Manchester: A transition occurs at the middle of the bit-interval (High to Low for 1, Low to High for 0).

- Differential Manchester: A transition always occurs in the middle of the bit interval; an additional transition at the beginning indicates a 0, while no transition indicates a 1.

- Block Coding: This process handles bits in groups, such as:

- 4B/5B Encoding: This maps 4 bits of code to 5 bits, ensuring a minimum number of 1s for clock synchronization.

- 8B/6T Encoding: This uses more than 3 voltage levels (e.g., 6 levels) to represent 8 bits per signal, allowing for more bits per signal.

These various encoding methods ensure efficient and reliable transmission of raw bits across diverse physical media.

How Do Protocol Data Units Change Across Network Layers?

The Transformation of PDUs

Network communication involves a dynamic process where data transforms as it traverses different layers of the OSI model. This transformation ensures data is properly formatted and addressed for each stage of its journey. A Protocol data unit undergoes significant changes as it moves from the application layer down to the physical layer, and then back up again at the receiving end.

Data Encapsulation and Decapsulation

The primary mechanism for PDU transformation is encapsulation. As application data moves down the OSI model layers on the sending device, each layer adds its own specific control information, typically in the form of a header and sometimes a trailer. This process effectively wraps the data from the upper layer within the PDU of the current layer. For instance, in a data center, a server sending information encapsulates it layer by layer.

Here is how data transforms through the layers:

- Application Layer: User applications generate the initial data or message.

- Transport Layer: This layer adds a TCP or UDP header. This header includes port numbers, sequence/acknowledgment numbers (for TCP), or source/destination ports, length, and checksum (for UDP). This forms a Segment (TCP) or Datagram (UDP).

- Network Layer: It encapsulates the transport segment with an IP header. This header contains source/destination IP addresses, Time to Live (TTL), and protocol identifiers. This creates a Packet.

- Data Link Layer: This layer forms a frame by adding a header (with source/destination MAC addresses) and a trailer (with a Frame Check Sequence for error detection).

- Physical Layer: It converts the complete frame into electrical signals, light pulses, or radio waves for transmission as Bits.

At the receiving device, the reverse process, known as decapsulation, occurs. Each layer removes its corresponding header and trailer, passing the remaining data up to the next higher layer. This continues until the original application data reconstructs at the application layer.

The following table summarizes the PDU terminology at each network layer:

| Network Layer | PDU Terminology |

|---|---|

| Application Layer | Data or Message |

| Transport Layer | Segment (TCP) or Datagram (UDP) |

| Network Layer | Packet |

| Data Link Layer | Frame |

| Physical Layer | Bits |

Header and Trailer Modifications

Each layer’s encapsulation process involves adding specific headers and, occasionally, trailers. These additions modify the overall size and structure of the PDU. Each header contains control information relevant only to its specific layer. This layered addition of information increases the total size of the data unit as it moves down the stack.

Consider a typical data flow:

- Application Data: This is the initial application information.

- TCP Header: A 20-byte TCP header is added to the application data.

- IP Header: Another 20-byte IP header is added, encapsulating the TCP header and data.

- Ethernet Frame: An Ethernet frame wraps around all of this, adding a 14-byte header and a 4-byte Frame Check Sequence (FCS) trailer.

This process demonstrates how each layer adds its own header (and sometimes a trailer), increasing the overall size of the PDU. For example, a normal Ethernet frame has a maximum size of 1,500 bytes. This includes the TCP data (up to 1,460 bytes), a 20-byte TCP header, a 20-byte IP header, a 14-byte Ethernet header, and a 4-byte FCS. These modifications ensure each layer has the necessary information to perform its functions, such as routing, error checking, and flow control, as data travels through a network infrastructure like a data center.

Why are Protocol Data Units Important for Network Communication?

The Critical Role of PDUs

Protocol Data Units (PDUs) are indispensable for modern network communication. They provide the fundamental structure and mechanisms that allow diverse devices to exchange information reliably and efficiently. Without PDUs, network communication would be chaotic and prone to errors. They ensure data travels correctly from source to destination, even across complex network infrastructures like large data centers.

Structured Data Exchange

PDUs establish a standardized format for data exchange. This structured approach ensures effective communication between devices. They manage information flow by segmenting data into manageable units. This simplifies error handling and data integrity. For example, when a server in a data center sends a large file, PDUs break it into smaller, organized pieces. This ensures efficient use of network resources by sending data in optimal sizes. It maintains high-speed communication and reduces latency. This structured format also enhances clarity and impact in crucial data conversations. It prevents rambling or omission of vital information.

Ensuring Data Integrity and Error Management

PDUs play a critical role in ensuring data integrity and managing errors during transmission. Error detection and correction are fundamental functions. Mechanisms like checksums or Cyclic Redundancy Checks (CRC) are incorporated into PDUs. These robust integrity checks safeguard data against corruption from noise, hardware malfunctions, or transmission errors. PDUs protect data integrity through verification. They ensure data packets are well-formed, properly ordered, and error-free. If a PDU is corrupted, the receiving device can detect the fault. This enables reliable data exchange by allowing retransmission of faulty data or correction of errors. This process ensures the received information is accurate, which is vital for critical data transfers in a data center.

Facilitating Interoperability

PDUs facilitate interoperability across diverse network systems. They dictate a universal format for encoding data. This ensures efficient processing and transmission between devices. The layered structure of PDUs ensures reliability, compatibility, and independence between hardware and software. It also provides a clear separation of responsibilities. This allows different systems and technologies to exchange data meaningfully. It maintains communication protocols. Protocol interoperability ensures consistent communication between devices from different vendors. This is crucial in complex environments where equipment from various manufacturers must work together seamlessly.

What is Encapsulation in the Context of Protocol Data Units?

The Process of PDU Encapsulation

Encapsulation describes the process where each layer of the OSI model adds its own control information to data as it moves down the stack. This process prepares data for transmission across a network. Each layer requests services from the layer directly below it. The lower layer then wraps the higher layer’s data by adding a header. Data Link protocols also add a trailer. The OSI model uses the term Protocol data unit (PDU) to refer to a unit of data that includes headers, trailers, and the encapsulated data for a specific layer. PDUs are numbered from 1 to 7, corresponding to the OSI layers. For example, a Layer 3 PDU refers to data encapsulated at the Network layer.

Adding Headers and Trailers Layer by Layer

Encapsulation begins at the Application layer. User data does not initially receive additional information here. As data moves down the layers, each layer adds its specific control information:

- Encapsulation begins at the Application layer (or Application, Presentation, Session layers in OSI) where no additional information is initially added to the user’s data.

- At the Transport layer, data segments. A header containing details like source/destination ports and sequence numbers is added. This encapsulated data is called Segments (for TCP) or Datagrams (for UDP).

- Moving to the Network layer, a Layer 3 header is appended. This includes source and destination IP addresses. The data at this stage is referred to as Packets.

- In the Data Link layer, a Layer 2 header and a trailer are added. The header contains MAC addresses, while the trailer is used for error checking. The encapsulated data here is known as Frames.

- Finally, the Physical layer receives these frames. It converts them into Bits for transmission.

This layered addition of headers and trailers ensures that each network device along the path understands how to process and forward the data.

Protecting and Directing Data

Encapsulation plays a vital role in protecting and directing data across the network. It ensures data integrity by adding headers and trailers that include error-checking information. These mechanisms include checksums and CRC values. This process helps detect and correct errors, thereby improving data integrity. For example, in a data center, a server sending critical financial data relies on these checks to ensure the information arrives uncorrupted.

For proper routing, encapsulation involves adding protocol-specific headers with addressing information at each layer of the OSI model. Network devices utilize this addressing information to make informed forwarding decisions. This ensures data reaches its correct destination.

- The Internet Layer adds IP addressing information (source/destination IP addresses, TTL values) to facilitate routing decisions and packet forwarding across networks.

- The Network Access Layer adds local network addressing information, such as MAC addresses. It also includes Frame Check Sequence trailers for error detection in Ethernet frames.

This comprehensive approach allows data to travel reliably and efficiently from its source to its destination, even across complex and diverse network infrastructures.

What is Decapsulation and How Does it Work with Protocol Data Units?

Decapsulation is the reverse process of encapsulation. It involves the receiver removing headers and trailers from data units as they ascend the network stack layers. This process ultimately reveals the original data payload for processing by the next higher layer. At the receiving end, decapsulation occurs as the corresponding header is stripped off at the same layer it was originally attached during encapsulation.

The Process of PDU Decapsulation

Removing Headers and Trailers

The decapsulation process moves in reverse order, from Layer 1 to Layer 7 in the OSI model, as the packet travels to the receiving computer.

- Layer 1: Physical: This layer manages electrical signals. It handles the bit sequence that marks the beginning and end of a packet.

- Layer 2: Data Link: This layer manages interactions across the local network. It handles the local destination address in the header. After stripping the header, trailer removal occurs primarily at this layer. The Data Link layer processes the header for addressing and metadata. It then uses the trailer for integrity checks.

- Layer 3: Network: This layer routes the packet across the network. It deals with the internet address header.

- Layer 4: Transport: This layer handles transport protocols like TCP or UDP. It adds byte counts to headers.

- Layer 5: Session: This layer manages the flow of information between systems. It provides details on how information is allowed to flow.

- Layer 6: Presentation: This layer modifies information into a format usable by an application. It provides details about data formats.

- Layer 7: Application: As the highest layer, this layer interacts directly with the end device.

Reconstructing the Original Data

Decapsulation verifies data integrity through checksums and other verification methods at each layer. Packets failing validation are discarded; error notifications may be sent. Trailer removal and integrity checks are crucial. The trailer contains error-detection information like a Frame Check Sequence (FCS). The system extracts and analyzes this to confirm frame validity. This typically involves a Cyclic Redundancy Check (CRC). The receiving device recomputes the CRC value over the protected portion of the frame. It compares this against the received FCS value. Standards like IEEE 802.3 for Ethernet frames specify a 32-bit CRC-32 polynomial for the FCS.

If the recalculated CRC matches the trailer’s value, the system deems the frame error-free. The system discards the trailer. It forwards the payload to the Network layer. If CRC values mismatch, indicating transmission errors, the system silently discards the entire frame. This prevents corrupted data from affecting higher-level protocols. Retransmission responsibility falls to transport-layer mechanisms, such as TCP, not the Data Link layer.

Header removal is the initial and core step, reversing encapsulation. The process begins at the lowest layer, physical or data link. The system examines and validates the incoming data unit before stripping its header. This sequential upward progression ensures each layer processes relevant information. It validates data before forwarding the Service Data Unit (SDU) to the next higher layer. During header inspection, the receiving layer scrutinizes key fields for errors. It extracts details like routing information or protocol identifiers. This determines the correct upper-layer protocol. This verifies validity, facilitates routing, and detects errors, potentially leading to discarding corrupted data units. Layers use parsing mechanisms to interpret fields like length indicators or delimiters. This defines the boundary between the header and the encapsulated payload. This allows precise header excision without altering the underlying data. It ensures clean SDU extraction, especially in variable-length protocols. Header removal transforms the received data unit into an SDU suitable for the upper layer. This enables seamless peer-to-peer interactions across the network stack. This step-by-step unveiling supports modular protocol design. Each layer contributes to end-to-end delivery. Trailer verification complements this process for integrity checks.

The operating system’s network stack processes layers three through seven. At the Network layer, the system examines the IP header. It verifies the destination IP address and extracts routing information. After validation, the system removes the IP header. It determines the appropriate Transport layer protocol. For TCP packets, the system examines sequence numbers, acknowledgment numbers, and window sizes before removing the TCP header. UDP processing involves basic header validation before removal. The Session, Presentation, and Application layers handle protocol-specific processing. This includes encryption/decryption, data compression, or format conversion. They then deliver the final payload to the destination application. For example, in a data center, a server receiving a large database update undergoes this precise decapsulation process. This ensures data integrity and correct application delivery.

This journey through Protocol Data Units reveals their fundamental role in network communication. They structure data, ensuring integrity and enabling seamless interoperability across diverse systems. From bits to frames, packets, and segments, PDUs facilitate every data exchange, like those within a data center. Understanding these units empowers a clearer comprehension of how networks function.

FAQ

What is the difference between a PDU and a packet?

A PDU is a general term for data at any OSI layer. A packet is a specific type of PDU at the network layer. For example, a server in a data center sends data as packets, but the transport layer handles segments, which are also PDUs.

Why do PDUs change across layers?

PDUs change to add specific control information for each layer’s function. This process, called encapsulation, ensures proper routing, error checking, and delivery. Each layer wraps the data with its own header, like adding shipping labels at different stages.

What is the smallest PDU?

The smallest PDU is a bit, found at the physical layer. It represents a single binary 0 or 1. All network communication, even complex data transfers in a data center, ultimately breaks down into these fundamental bits for transmission.

How does a PDU help with error detection?

PDUs include error-checking mechanisms like checksums or Frame Check Sequences (FCS) in their headers or trailers. The receiving device uses these to verify data integrity. If a PDU is corrupted, the system detects the error and can request retransmission.

Can a PDU be lost?

Yes, PDUs can be lost during transmission due to network congestion, hardware failures, or errors. Protocols like TCP at the transport layer use acknowledgments and retransmissions to ensure reliable delivery of segments, preventing data loss in critical data center operations.

What is the role of PDUs in a data center?

PDUs are fundamental in a data center. They structure all data exchanged between servers, storage, and clients. They ensure efficient, reliable, and secure communication for applications, databases, and virtual machines. Every byte of data moves within a PDU.

Post time: Jan-16-2026